Each house at Totem Park Residence was named to honour Indigenous peoples in British Columbia. The newest houses carry place names gifted by our host, the Musqueam Nation, but the original six do not.

These two sets of houses represent very different approaches to working with Indigenous communities and provide important lessons for all of us. Please take a moment to begin learning about the history and meaning of these names, and how they should be used.

What is the Power of a Name?

There are 203 First Nations in British Columbia. To recognize some of these diverse communities, the first six houses at Totem Park Residence were named Haida, Salish, Nootka, Dene, Kwakiutl and Shuswap in the 1960s. While the University had good intentions, no Indigenous communities were involved in the naming process nor asked for their permission. As a result, generic anthropological terms were used, and the names Nootka, Kwakiutl, Shuswap and Salish are inaccurate. The first three names should refer to the Nuu-chan-nulth, Kwakwa̱ka̱’wakw and Secwepemc nations, while Salish recognizes the Coast Salish peoples, a very broad category that encompasses a large number of communities across Canada and the United States rather than one specific community or place.

“Aboriginal people have their own names for their territories and places. European explorers and settlers did not learn these names but invented their own instead. This is one way that Europeans re-wrote history and excluded Aboriginal people. For example, the city of Vancouver is named after Captain George Vancouver, who was born in England in 1757, and not after a Chief of the territory whose family had lived in Vancouver forever.”

“Some Vancouver place names used today are English versions of Aboriginal words. Often these Aboriginal words were not place names. Naming places after faraway places or people who have never lived there is a European, not Aboriginal, custom.”

The original naming process also did not recognize the fact that UBC Vancouver is located on the traditional, ancestral, and unceded territory of the Musqueam people. In 2011, Student Housing and Community Services began working with the Musqueam Nation to name the new infill houses at Totem Park Residence, and educate students about the true history of the land they are living on. Through a collaborative naming and storytelling process, Musqueam gifted the names həm̓ləsəm̓ and q̓ələχən in 2011, and the name c̓əsnaʔəm in 2017, for use at Totem Park Residence. These are three of the place names within their territory that carry important stories.

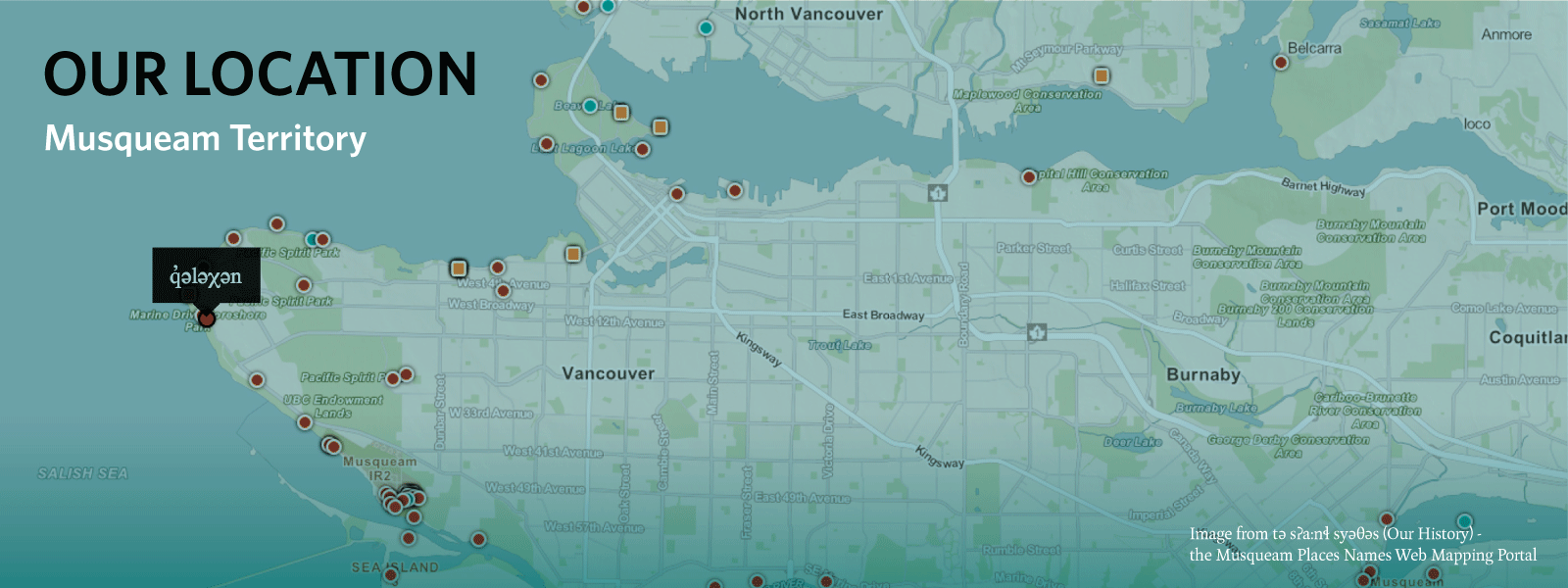

Musqueam Territory

UBC Vancouver is located on the traditional, ancestral and unceded territory of the Musqueam (xʷməθkʷəy̓əm) people. Musqueam’s traditional territory encompasses what is now Vancouver and surrounding areas. Today, portions of Musqueam’s traditional territory are called Vancouver, North Vancouver, South Vancouver, Burrard Inlet, New Westminster, Burnaby, and Richmond.

Visit Musqueam’s interactive place names map.

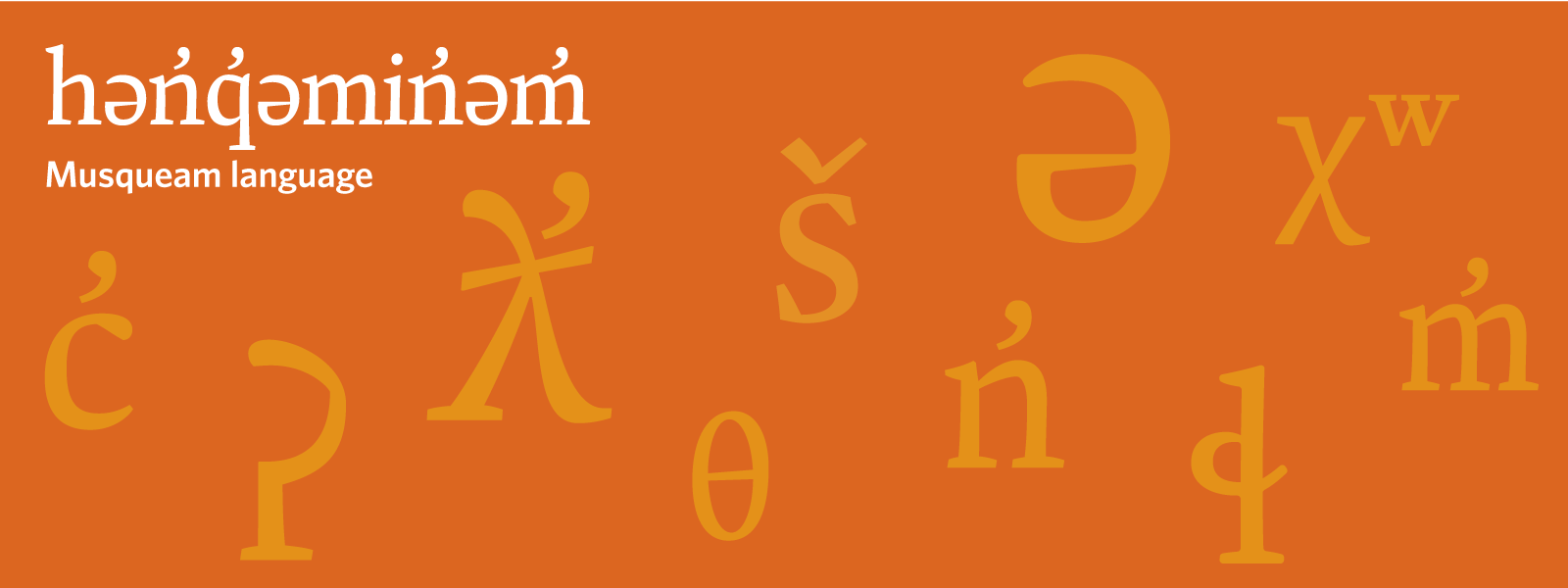

About the Musqueam Language

The Musqueam community formally adopted the North American Phonetic Alphabet (NAPA) because of its specialized symbols that are designed to be an accurate language documentation and teaching tool. The Musqueam language, hən̓q̓əmin̓əm̓, contains 36 consonants, 22 not appearing in English and some appearing in only a handful of languages around the world.

Learn more about the hən̓q̓əmin̓əm̓ language:

- Explore the hən̓q̓əmin̓əm̓ alphabet

- Visit the hən̓q̓əmin̓əm̓ pronunciation guide

House Name Origins

Storytelling Initiatives

The Musqueam-SHCS (Student Housing and Community Services) Storytelling Committee, whose members worked together to name c̓əsnaʔəm House in 2017, has been developing educational materials and opportunities for students to learn more about the land, language, culture, and history of the Musqueam people.

Here is a photo gallery of some of the beautiful indoor and outdoor pieces that were installed throughout Totem Park.

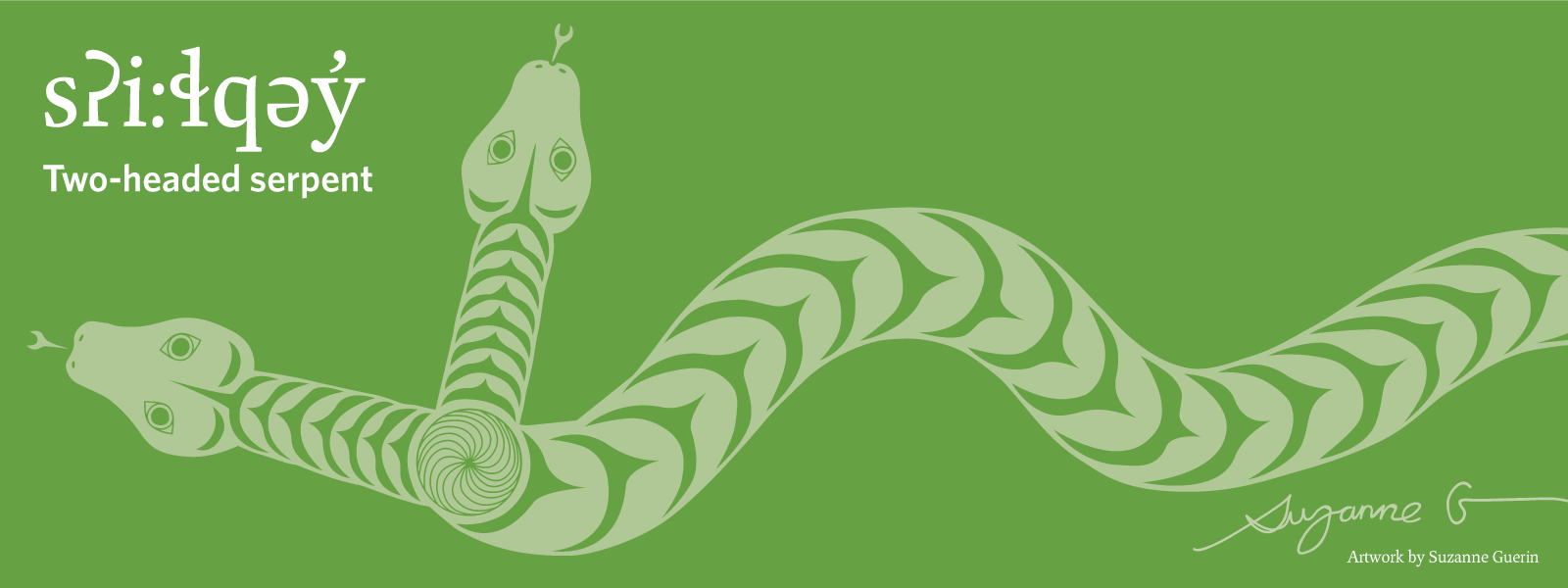

Two Headed Serpent

The double-headed serpent is a central figure in the origin story of name xʷməθkʷəy̓əm (Musqueam). This design featured at c̓əsnaʔəm House as a 40-foot window decal was originally sketched by young Musqueam artist Suzanne Guerin with pencil on paper.

A house post* of the doubled-headed serpent named sʔ:iɬqəy̓ is located adjacent to the Bookstore in the University Commons. It was carved by Brent Sparrow Jr. and raised on April 6, 2016.

Learn more about the Musqueam Post.

Watch a short animation of Suzanne’s design here—or see it in person at the Museum of Vancouver.

*Did you know there are different types of carving traditions? Many Coast Salish communities, including Musqueam, carve house posts, which are distinct from totem poles.

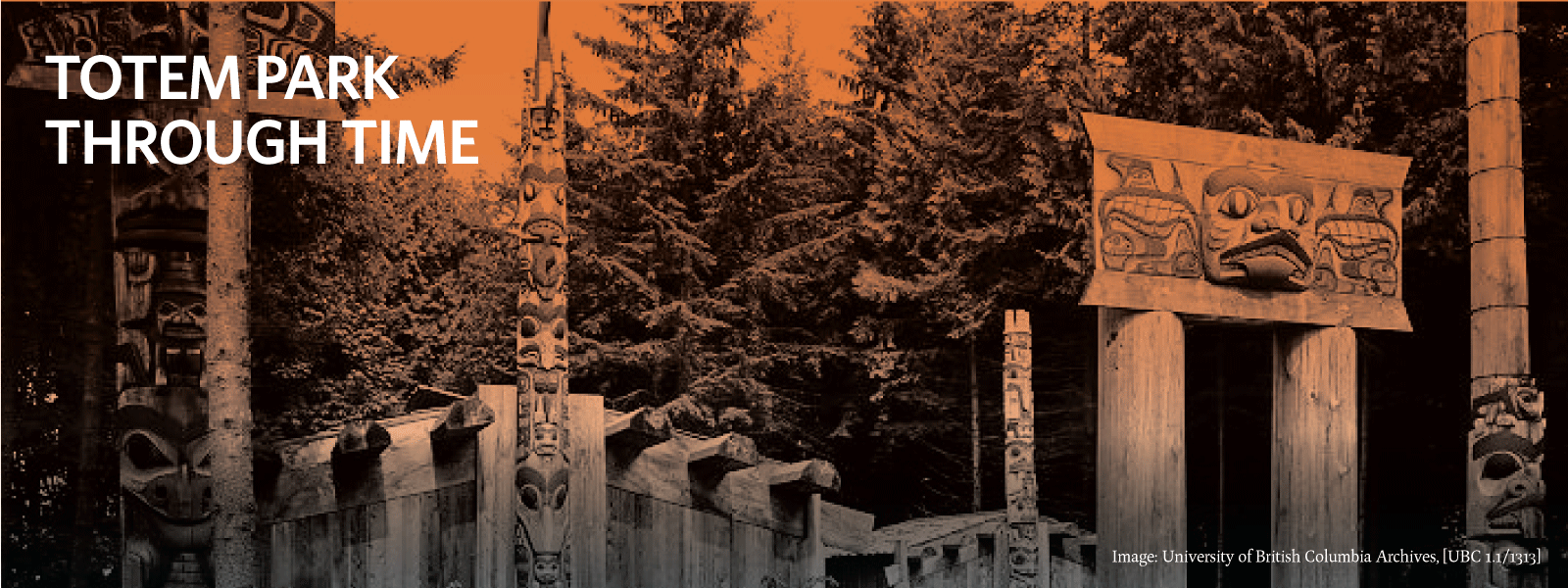

Totem Park Through Time

The area that Totem Park Residence occupies today used to be the site of an outdoor exhibit called “Totem Pole Park.” This park displayed work by renowned artists Bill Reid (Haida) and Douglas Cranmer (Kwakwa̱ka̱’wakw), and was relocated to UBC’s Museum of Anthropology just prior to the construction of the residence. Explore the transformation of this site through time.

The Musqueam people were not consulted during the creation of this park, and thus there was no Musqueam representation in this space originally. Totem poles are not part of their tradition, but are used by other nations who have heraldic clans. Instead, there is a rich tradition of carving house posts within the Musqueam community, either in the construction of traditional longhouses or exterior to homes and buildings.

c̓səmlenəxʷ post

The c̓səmlenəxʷ post, a Musqueam house post installed at Totem Park in 1974/75, is located immediately south of the commonsblock. Identified on its plaque as Man Meets Bear, the post is a reiteration of the “historical c̓səmlenəxʷ board on display inside the Museum of Anthropology.”*

To learn more about the c̓səmlenəxʷ post and other Musqueam house posts at UBC, download Jordan Wilson’s qeqən: A Walking Tour of Musqueam House Posts.

*from qeqən: A Walking Tour of Musqueam House Posts, by Jordan Wilson